Economics of the Environment: Selected Readings (Sixth Edition)

Environmental economic science is a sub-field of economics concerned with environmental issues. It has become a widely studied subject due to growing environmental concerns in the twenty-outset century. Ecology economics "undertakes theoretical or empirical studies of the economic effects of national or local environmental policies around the globe. ... Particular issues include the costs and benefits of alternative ecology policies to deal with air pollution, water quality, toxic substances, solid waste product, and global warming."[1]

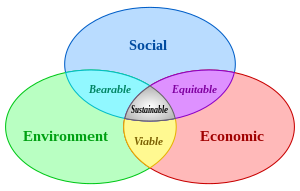

Environmental economics is distinguished from ecological economics in that ecological economics emphasizes the economy as a subsystem of the ecosystem with its focus upon preserving natural capital.[two] One survey of German economists establish that ecological and environmental economic science are dissimilar schools of economic idea, with ecological economists emphasizing "strong" sustainability and rejecting the proposition that human-fabricated ("concrete") uppercase tin can substitute for natural capital.[3]

History [edit]

The modern field of ecology economic science has been traced to the 1960s.[iv]

Topics and concepts [edit]

Marketplace failure [edit]

Air pollution is an example of market failure, equally the mill is imposing a negative external toll on the community.

Central to environmental economics is the concept of market failure. Market failure means that markets fail to allocate resources efficiently. As stated past Hanley, Shogren, and White (2007):[5] "A market failure occurs when the market does non allocate scarce resources to generate the greatest social welfare. A wedge exists between what a private person does given market prices and what society might want him or her to do to protect the surround. Such a wedge implies wastefulness or economic inefficiency; resources can be reallocated to make at least one person better off without making anyone else worse off." Common forms of market failure include externalities, non-excludability and non-rivalry.[6]

Externality [edit]

An externality exists when a person makes a choice that affects other people in a manner that is non deemed for in the market cost. An externality can be positive or negative merely is ordinarily associated with negative externalities in environmental economics. For instance, h2o seepage in residential buildings occurring in upper floors affect the lower floors.[vii] Some other instance concerns how the sale of Amazon timber disregards the amount of carbon dioxide released in the cutting.[8] [ meliorate source needed ] Or a house emitting pollution will typically non have into business relationship the costs that its pollution imposes on others. As a outcome, pollution may occur in excess of the 'socially efficient' level, which is the level that would exist if the market was required to account for the pollution. A classic definition influenced by Kenneth Pointer and James Meade is provided by Heller and Starrett (1976), who ascertain an externality as "a situation in which the private economy lacks sufficient incentives to create a potential market place in some good and the nonexistence of this market results in losses of Pareto efficiency".[9] In economical terminology, externalities are examples of market failures, in which the unfettered market place does not lead to an efficient outcome.

Common goods and public goods [edit]

When information technology is likewise plush to exclude some people from access to an environmental resource, the resource is either called a common property resources (when there is rivalry for the resources, such that one person's utilise of the resource reduces others' opportunity to utilize the resource) or a public adept (when apply of the resources is non-rivalrous). In either example of non-exclusion, marketplace allocation is likely to be inefficient.

These challenges have long been recognized. Hardin's (1968) concept of the tragedy of the eatables popularized the challenges involved in not-exclusion and common holding. "Commons" refers to the environmental nugget itself, "common property resource" or "common pool resources" refers to a holding right authorities that allows for some collective body to devise schemes to exclude others, thereby allowing the capture of futurity do good streams; and "open-admission" implies no ownership in the sense that property everyone owns nobody owns.[10]

The basic problem is that if people ignore the scarcity value of the commons, they can end upwards expending too much try, over harvesting a resource (e.grand., a fishery). Hardin theorizes that in the absenteeism of restrictions, users of an open-admission resource will use it more than if they had to pay for it and had exclusive rights, leading to environmental degradation. See, however, Ostrom'southward (1990) work on how people using real common property resources have worked to establish self-governing rules to reduce the risk of the tragedy of the commons.[ten]

The mitigation of climate change furnishings is an example of a public proficient, where the social benefits are not reflected completely in the market cost. This is a public good since the risks of climate change are both not-rival and non-excludable. Such efforts are non-rival since climate mitigation provided to 1 does not reduce the level of mitigation that anyone else enjoys. They are non-excludable actions equally they will have global consequences from which no one can be excluded. A country'southward incentive to invest in carbon abatement is reduced considering it can "free ride" off the efforts of other countries. Over a century agone, Swedish economist Knut Wicksell (1896) showtime discussed how public appurtenances can be under-provided past the market because people might conceal their preferences for the proficient, but still enjoy the benefits without paying for them.

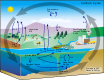

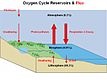

- Global biochemical cycles

-

-

-

-

Valuation [edit]

Assessing the economic value of the environs is a major topic within the field. The values of natural resources frequently are not reflected in prices that markets fix and, in fact, many of them are available at no monetary charge. This mismatch frequently causes distortions in pricing of natural avails: both overuse of them and underinvestment in them.[11] Economic value or tangible benefits of ecosystem services and, more than by and large, of natural resources, include both utilise and indirect (meet the nature section of ecological economics). Not-use values include existence, choice, and bequest values. For example, some people may value the existence of a diverse set of species, regardless of the consequence of the loss of a species on ecosystem services. The existence of these species may have an option value, as there may exist the possibility of using information technology for some human being purpose. For instance, sure plants may be researched for drugs. Individuals may value the ability to leave a pristine environs for their children.

Use and indirect apply values tin can ofttimes be inferred from revealed behavior, such equally the toll of taking recreational trips or using hedonic methods in which values are estimated based on observed prices. Non-utilize values are usually estimated using stated preference methods such equally contingent valuation or choice modelling. Contingent valuation typically takes the grade of surveys in which people are asked how much they would pay to observe and recreate in the surroundings (willingness to pay) or their willingness to accept (WTA) compensation for the destruction of the ecology good. Hedonic pricing examines the effect the environment has on economic decisions through housing prices, traveling expenses, and payments to visit parks.[12]

State subsidy [edit]

Almost all governments and states magnify ecology harm by providing various types of subsidies that take the effect of paying companies and other economic actors more to exploit natural resources than to protect them. The harm to nature of such public subsidies has been conservatively estimated at $4-$6 trillion U.S. dollars per year.[xiii]

Solutions [edit]

Solutions advocated to correct such externalities include:

- Ecology regulations. Under this plan, the economic affect has to be estimated by the regulator. Usually, this is done using cost-benefit analysis. There is a growing realization that regulations (too known as "command and control" instruments) are not then distinct from economic instruments as is commonly asserted by proponents of environmental economics. Eastward.yard.1 regulations are enforced by fines, which operate as a form of tax if pollution rises above the threshold prescribed. Eastward.thousand.2 pollution must be monitored and laws enforced, whether nether a pollution tax regime or a regulatory regime. The master difference an ecology economist would argue exists between the two methods, however, is the total cost of the regulation. "Command and control" regulation ofttimes applies compatible emissions limits on polluters, fifty-fifty though each firm has different costs for emissions reductions, i.east., some firms, in this system, can allay pollution inexpensively, while others tin simply abate it at high cost. Because of this, the total abatement in the system comprises some expensive and some inexpensive efforts. Consequently, modern "Control and command" regulations are oftentimes designed in a style that addresses these issues by incorporating utility parameters. For example, COtwo emission standards for specific manufacturers in the automotive industry are either linked to the boilerplate vehicle footprint (US system) or boilerplate vehicle weight (European union organization) of their entire vehicle fleet. Environmental economic regulations detect the cheapest emission abatement efforts first, and then move on to the more than expensive methods. E.g. every bit said earlier, trading, in the quota system, means a business firm only abates pollution if doing so would cost less than paying someone else to make the same reduction. This leads to a lower cost for the full abatement effort as a whole.[ commendation needed ]

- Quotas on pollution. Oft it is advocated that pollution reductions should exist achieved by way of tradeable emissions permits, which if freely traded may ensure that reductions in pollution are achieved at least cost. In theory, if such tradeable quotas are allowed, and so a firm would reduce its ain pollution load only if doing so would cost less than paying someone else to make the aforementioned reduction, i.e., only if ownership tradeable permits from another firm(south) is costlier. In practice, tradeable permits approaches have had some success, such as the U.S.'southward sulphur dioxide trading program or the European union Emissions Trading Scheme, and interest in its application is spreading to other environmental problems.

- Taxes and tariffs on pollution. Increasing the costs of polluting will discourage polluting, and volition provide a "dynamic incentive", that is, the disincentive continues to operate fifty-fifty as pollution levels fall. A pollution taxation that reduces pollution to the socially "optimal" level would exist fix at such a level that pollution occurs only if the benefits to gild (for example, in form of greater production) exceeds the costs. This concept was introduced past Arthur Pigou, a British economist active in the belatedly nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century. He showed that these externalities occur when markets fail, pregnant they do not naturally produce the socially optimal corporeality of a good or service. He argued that "a tax on the production of paint would encourage the [polluting] mill to reduce production to the corporeality best for society as a whole."[14] These taxes are known amongst economists as Pigouvian Taxes, and they regularly implemented where negative externalities are present. Some abet a major shift from taxation from income and sales taxes to tax on pollution - the then-called "dark-green tax shift".

- Meliorate defined property rights. The Coase Theorem states that assigning property rights volition pb to an optimal solution, regardless of who receives them, if transaction costs are trivial and the number of parties negotiating is limited. For example, if people living virtually a manufactory had a right to clean air and water, or the factory had the right to pollute, then either the factory could pay those affected by the pollution or the people could pay the factory not to pollute. Or, citizens could take action themselves as they would if other property rights were violated. The US River Keepers Law of the 1880s was an early example, giving citizens downstream the right to end pollution upstream themselves if the government itself did not human action (an early case of bioregional democracy). Many markets for "pollution rights" have been created in the tardily twentieth century—see emissions trading. According to the Coase Theorem, the involved parties volition deal with each other, which results in an efficient solution. However, modern economic theory has shown that the presence of asymmetric information may lead to inefficient bargaining outcomes.[15] Specifically, Rob (1989) has shown that pollution claim settlements volition non lead to the socially optimal issue when the individuals that will be affected past pollution have learned individual data about their disutility already earlier the negotiations take identify.[16] Goldlücke and Schmitz (2018) have shown that inefficiencies may also result if the parties larn their private information only subsequently the negotiations, provided that the feasible transfer payments are bounded.[17]

Relationship to other fields [edit]

Ecology economics is related to ecological economics but at that place are differences. Most environmental economists have been trained as economists. They apply the tools of economic science to accost environmental issues, many of which are related to so-chosen market failures—circumstances wherein the "invisible mitt" of economics is unreliable. Most ecological economists have been trained every bit ecologists, but have expanded the scope of their work to consider the impacts of humans and their economical activity on ecological systems and services, and vice versa. This field takes every bit its premise that economics is a strict subfield of ecology. Ecological economics is sometimes described as taking a more pluralistic approach to environmental problems and focuses more explicitly on long-term environmental sustainability and issues of scale.

Ecology economics is viewed as more businesslike in a price system; ecological economics as more idealistic in its attempts not to use money as a primary arbiter of decisions. These ii groups of specialists sometimes accept conflicting views which may be traced to the different philosophical underpinnings.

Another context in which externalities employ is when globalization permits 1 player in a market who is unconcerned with biodiversity to undercut prices of another who is - creating a race to the lesser in regulations and conservation. This, in turn, may crusade loss of natural capital with consequent erosion, water purity problems, diseases, desertification, and other outcomes that are not efficient in an economical sense. This concern is related to the subfield of sustainable development and its political relation, the anti-globalization motion.

Environmental economics was once distinct from resources economics. Natural resources economics as a subfield began when the principal business organisation of researchers was the optimal commercial exploitation of natural resource stocks. Merely resource managers and policy-makers eventually began to pay attention to the broader importance of natural resources (due east.g. values of fish and copse beyond only their commercial exploitation). It is now difficult to distinguish "environmental" and "natural resource" economics as divide fields as the 2 became associated with sustainability. Many of the more radical green economists split off to work on an alternate political economy.

Environmental economics was a major influence on the theories of natural capitalism and environmental finance, which could be said to be ii sub-branches of environmental economic science concerned with resource conservation in production, and the value of biodiversity to humans, respectively. The theory of natural capitalism (Hawken, Lovins, Lovins) goes further than traditional ecology economic science past envisioning a globe where natural services are considered on par with concrete capital letter.

The more radical green economists pass up neoclassical economics in favour of a new political economic system beyond capitalism or communism that gives a greater emphasis to the interaction of the homo economy and the natural environment, acknowledging that "economy is three-fifths of ecology" - Mike Nickerson. This political group is a proponent of a transition to renewable energy.

These more than radical approaches would imply changes to coin supply and likely also a bioregional democracy so that political, economical, and ecological "ecology limits" were all aligned, and not subject to the arbitrage normally possible under capitalism.

An emerging sub-field of ecology economic science studies its intersection with development economic science. Dubbed "envirodevonomics" by Michael Greenstone and B. Kelsey Jack in their paper "Envirodevonomics: A Research Agenda for a Immature Field", the sub-field is primarily interested in studying "why environmental quality [is] so poor in developing countries."[18] A strategy for meliorate agreement this correlation between a country's GDP and its environmental quality involves analyzing how many of the primal concepts of environmental economics, including market failures, externalities, and willingness to pay, may be complicated by the detail problems facing developing countries, such as political issues, lack of infrastructure, or inadequate financing tools, among many others.[19]

In the field of law and economic science, ecology law is studied from an economic perspective. The economic analysis of ecology police force studies instruments such as zoning, expropriation, licensing, third party liability, safety regulation, mandatory insurance, and criminal sanctions. A book past Michael Faure (2003) surveys this literature.[20]

Professional bodies [edit]

The main academic and professional organizations for the subject field of Environmental Economics are the Association of Ecology and Resource Economists (AERE) and the European Clan for Environmental and Resource Economics (EAERE). The primary academic and professional organisation for the subject area of Ecological Economics is the International Guild for Ecological Economics (ISEE). The primary arrangement for Light-green Economics is the Greenish Economic science Institute.

Come across as well [edit]

- Agricultural ecology

- Carbon fee and dividend

- Carbon finance

- Carbon negative fuel

- Circular economy

- Earth Economic science (policy retrieve tank)

- Eco-capitalism

- Eco commerce

- Economics of global warming

- Ecometrics

- Eco-Money

- Eco-socialism

- Ecosystem Marketplace

- Ecotax

- Energy balance

- Environmental accounting

- Environmental economists (category)

- Environmental credit crisis

- Ecology enterprise

- Environmental Investment Organisation

- Environmental pricing reform

- Ecology tariff

- Fair trade

- Financial environmentalism

- Free-market environmentalism

- Green cyberbanking

- Green libertarianism

- Green syndicalism

- Green trading

- Gross domestic product § Further criticisms

- ISO 14000 (environmental standards)

- List of scholarly journals in environmental economics

- Natural capital

- Natural resource

- Natural resource economics

- Principles of ecopreneurship

- Property rights (economics)

- Renewable resource

- Risk assessment

- Strategic Sustainable Investing (SSI)

- Systems ecology

- Globe Ecological Forum

Hypotheses and theorems [edit]

- Coase theorem

- Porter hypothesis

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Environmental Economics". NBER Working Group Descriptions. National Bureau of Economical Research. Retrieved 2006-07-23 .

- ^ Jeroen C.J.M. van den Bergh (2001). "Ecological Economics: Themes, Approaches, and Differences with Environmental Economics," Regional Environmental Change, 2(1), pp. xiii-23 Archived 2008-x-31 at the Wayback Machine (press +).

- ^ Illge L, Schwarze R. (2009). A Affair of Opinion: How Ecological and Neoclassical Environmental Economists Remember about Sustainability and Economics . Ecological Economics.

- ^ Pearce, David (2002). "An Intellectual History of Ecology Economics". Annual Review of Energy and the Surroundings. 27 (1): 57–81. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.27.122001.083429. ISSN 1056-3466.

- ^ Hanley, Due north., J. Shogren, and B. White (2007). Environmental Economic science in Theory and Practise, Palgrave, London.

- ^ Anderson, D. (2019). Environmental Economics and Natural Resource Management, [1] Routledge, New York.

- ^ Rita Yi Man Li (2012), The Internalisation Of Ecology Externalities Affecting Dwellings: A Review Of Court Cases In Hong Kong, Economic Diplomacy, Volume 32, Issue 2, pages 81–87

- ^ Chapman, Same (May 3, 2012). "Environmental degradation replaces classic imperialism". The Whitman Higher Pioneer: Whitman Higher.

- ^ Heller, Walter P. and David A. Starrett (1976), On the Nature of Externalities, in: Lin, Stephen A.Y. (ed.), Theory and Measurement of Economic Externalities, Academic Printing, New York, p.10

- ^ a b Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Eatables. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Great britain Authorities Official Documents, February 2021, "The Economic science of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review Headline Messages"

- ^ Harris J. (2006). Environmental and Natural Resource Economic science: A Contemporary Arroyo. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ UK Government Official Documents, February 2021, "The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review Headline Messages" p. 2

- ^ Kishtainy, Niall (2018-02-27). A little history of economics. ISBN9780300234527. OCLC 1039849897.

- ^ Myerson, Roger B; Satterthwaite, Mark A (1983). "Efficient mechanisms for bilateral trading" (PDF). Periodical of Economic Theory. 29 (ii): 265–281. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(83)90048-0. hdl:10419/220829. ISSN 0022-0531.

- ^ Rob, Rafael (1989). "Pollution claim settlements under private information". Periodical of Economic Theory. 47 (2): 307–333. doi:x.1016/0022-0531(89)90022-7. ISSN 0022-0531.

- ^ Goldlücke, Susanne; Schmitz, Patrick Due west. (2018). "Pollution merits settlements reconsidered: Hidden information and bounded payments". European Economic Review. 110: 211–222. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.08.005. ISSN 0014-2921.

- ^ Greenstone, Michael; Jack, B. Kelsey (2015). "Envirodevonomics: A Research Calendar for an Emerging Field". Journal of Economic Literature. 53 (one): 5–42. doi:10.1257/jel.53.ane.five. S2CID 73594686.

- ^ Inclusive light-green growth the pathway to sustainable development (PDF). Washington, D.C.: World Bank. May 2012. pp. 12–thirteen. ISBN978-0-8213-9552-3 . Retrieved 15 Jan 2015.

- ^ Faure, Michael Thou. (2003). The Economic Analysis of Environmental Policy and Law: An Introduction. Edward Elgar. ISBN9781843762348.

References [edit]

- Allen V. Kneese and Clifford Due south. Russell (1987). "environmental economics," The New Palgrave: A Lexicon of Economic science, v. ii, pp. 159–64.

- Robert N. Stavins (2008). "environmental economics," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract & article.

- Maureen 50. Cropper and Wallace East. Oates (1992). "Environmental Economic science: A Survey," Journal of Economic Literature, 30(ii), pp. 675-740(press +).

- Pearce, David (2002). "An Intellectual History of Environmental Economics". Almanac Review of Energy and the Surroundings. 27: 57–81. doi:x.1146/annurev.free energy.27.122001.083429.

- Tausch, Arno, 'Smart Evolution'. An Essay on a New Political Economy of the Environment (March 22, 2016). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2752988 or https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2752988

- UNEP (2007). Guidelines for Conducting Economical Valuation of Coastal Ecosystem Goods and Services, UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 8.

- UNEP (2007). Procedure for Decision of National and Regional Economical Values for Ecotone Goods and Services, and Full Economical Values of Littoral Habitats in the context of the UNEP/Global environment facility Project Entitled: "Reversing Ecology Degradation Trends in the South China Ocean and Gulf of Thailand", Due south Red china Sea Cognition Document No. 3. UNEP/Global environment facility/SCS/Inf.3

- Perman, Roger; et al. (2003). Natural Resource and Surroundings Economics (PDF) (3 ed.). Pearson. ISBN978-0273655596.

- Field, Barry (2017). Ecology economics : an introduction. New York, NY: McGraw-Loma. ISBN978-0-07-802189-3. OCLC 931860817.

Farther reading [edit]

- David A. Anderson (2019). Environmental Economics and Natural Resource Management 5e, [ii] New York: Routledge.

- John Asafu-Adjaye (2005). Environmental Economics for Non-Economists 2e, Singapore: World Scientific.

- Gregory C. Chow (2014). Economics Analysis of Environmental Bug, Singapore: World Scientific.

cousinlonswellot58.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental_economics

Post a Comment for "Economics of the Environment: Selected Readings (Sixth Edition)"